Situation: Financially secure Ontario couple with two jobs and one child wants more kids and move to Vancouver to be near parents

Solution: Examine B.C. housing cost and balance that with other financial goals

In eastern Ontario, a couple we’ll call Gary, 35, and Martha, 30, have a one-year-old child and parents in their late 70s who may eventually need income assistance and physical help. That pair of dependencies is typical of the so-called sandwich generation of young adults who have to be both parents to the young and caregivers to the old.

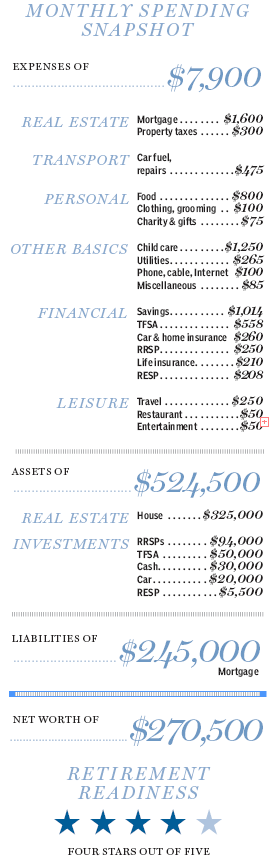

Martha is thinking of giving up her office management job with a large financial corporation. Her work contributes $4,300 a month after tax, more than half the family after-tax of $7,900. Her goal: have two more children. More kids would mean a higher cost of living and, if they move to Vancouver, as they would like, their present cost of shelter — $1,900 a month for their mortgage and property taxes — would probably soar. In the family’s favour is the work Gary does a market researcher. He could work at home and provide childcare, thus allowing Martha to stay on her job and grow the defined benefit pension that goes with it.

Email [email protected] for a free Family Finance analysis

“We want to move to one income,” Martha explains. “But we are worried that … may not be sufficient to get us to retirement when Gary is 60, especially if we have to help support our parents.” Both couples live on their own,

Family Finance asked Benoit Poliquin, a financial planner and chief investment officer of Exponent Investment Management Inc. in Ottawa, to work with Gary and Martha.

Poliquin lays out the situation: “The core questions for this couple are: 1) can they get by on one salary; 2) can they afford to sell their present home, buy another and pay costs of raising one or two more children and helping their parents; and 3) retire in 25 years when Gary is 60 and Martha is 55?”

Family planning

On the plus side, Gary and Martha are very effective savers. They bring home $7,900 a month, allocate $1,016 to RRSPs, RESPs and their TFSAs and then have $1,014 for general savings after all other expenses. To boost their TFSA contributions to $10,000 each, they could shift some cash from their general savings, but the total envelope of savings and investment would not be changed. Adding up all registered and other savings, they are saving $2,030 a month, which is a quarter of their take home income.

But can they live on one income? Martha will get almost a year of fully paid maternal leave from her employer and government benefits. When that ends, Gary can do part time work at home and take care of the children. His take-home income might decrease slightly from its present level of $3,600 a month, but the compensation would be saving the $1,250, a month, or $15,000 a year, they now spend on outside childcare.

Gary and Martha have one child, but hope to have two more. They have saved $5,500 in an RESP so far, including the Canada Education Savings Grant of 20 per cent of contributions to a $500 annual limit. If Gary and Martha continue to add $2,500 a year and get the $500 CESG and a three per cent return after inflation each year, the fund will have $71,100 when their one-year-old turns 18. That would cover four years of university and living at home. The parents can double or triple the contribution rate to $416 a month or $624 a month with the about same outcome for each child at the cost of reducing non-registered savings of $2,814 a month. We don’t know how many children there will be, so we’ll go with what is already in the present budget.

Heading west – is it affordable?

Moving to B.C. to be with the couple’s parents is another issue. Their $325,000 Ontario home is likely to cost twice that in the hinterlands and four times that in or near Vancouver. We’ll go with three times and round up to $1 million. Their present home equity and other savings could provide a down payment. They owe $245,000 which, at 2.85 per cent with the present 22-year amortization remaining, leaves them with $80,000 of equity. A $1 million house with a 10 per cent down payment and a 25-year amortization on a high ratio mortgage with a three per cent interest rate would cost $4,270 a month.

That would be difficult to support on their present income. With a $100,000 down payment, a $600,000 house with a $500,000 mortgage and 25 year amortization would cost $2,370 a month. They already pay $1,600, so the larger mortgage would be half as much again. It would be feasible at their present income with two parents working, difficult with one income at present level, but would provide a house fully paid by the time Gary is 60 and Martha is 55. The largest problem with this scenario would be finding a house they like within commuting distance of Vancouver, where their parents live.

Retirement plans

Martha’s employment comes with an indexed defined benefit pension plan. She can retire with an annual benefit of $47,000 in 2015 dollars. Retirement accounts will grow with continuing contributions. In 25 years, when Martha would retire at 55, total family RRSPs with a present value of $94,000 growing at three per cent a year and $3,000 of annual contributions would have a value of $309,475 in 2015 dollars. Their TFSAs, to which they contribute $558 a month as well as make irregular lump sum additions, with a present balance of $50,000, would be worth $356,000, and taxable savings, currently $30,000 in cash and growing at $1,014 a month, could be worth $520,000 if invested to generate three per cent a year after inflation.

The total of these accounts, $1,185,475, invested to yield three per cent after inflation on a perpetual basis, would generate $35,564 a year on top of the $47,000 job pension. They could add Canada Pension Plan benefits of $12,780 for Martha and $7,668 for Gary at 65, then Old Age Security at 67 of $6,765 each. After splits of eligible income, their pre-tax income would be $116,542. After 20 per cent average income tax, they would have $7,770 to spend each month. That would support present spending of $7,900 a month without $3,280 a month of savings, mortgage payments or childcare expense.

Were they to use an annuitized payout process that would expend all capital from her age 55 to the time Martha is 90 and Gary 95, still using a three per cent return, they would be able to have a $53,560 return from investments on top of Martha’s $47,000 job pension for a pre-tax total of $100,100. CPP and OAS would push total income to $134,540 in 2015 dollars. After splits of eligible income and 20 per cent average tax, they would have about $8,970 to spend each month.

Having one or two more children while their elderly parents are alive would be likely to reduce their savings rate by a third with one child and two thirds with two. They would need a larger house, need to double or triple money going to RESPs and tend to spend more on food, clothing, holidays, etc. On top of that, the potential need to help their parents with money of perhaps a few thousand dollars a month and to care for them suggests that they could not cope with the needs of a large, extended family. Prudence suggests keeping their family small, Poliquin says. If they do that and maintain their high level of savings, move west if they wish but buy a modest house, then they can spare a few thousand dollars a month for their parents if they need it and devote time to their care if they wish it.

“Martha’s job pension is the cornerstone that makes this couple’s retirement plans feasible,” Poliquin says. “The pension is substantial, defined and guaranteed. Giving up that job would add risk to their plans.”