Situation: Couple worries that wife’s one-year sabbatical will torpedo their retirement plans

Solution: Run the numbers and ensure that post-sabbatical income is sufficient for retirement

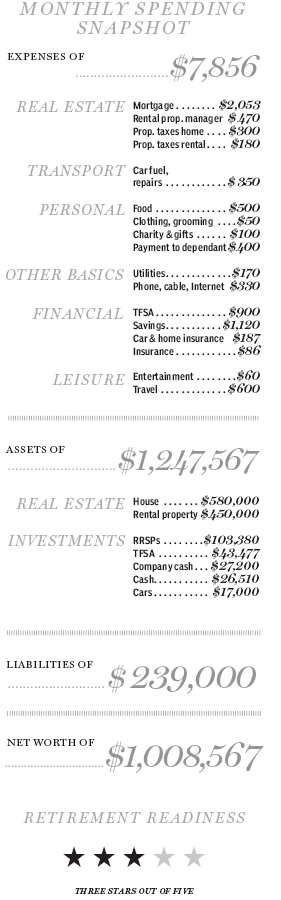

A couple we’ll call Hugh and Catherine, both 54, have a home in B.C.’s Lower Mainland. Each is engaged in the arts – Hugh as a stage designer, Catherine as a musician; they have no children, but they contribute financial support to Hugh’s mom. Their take-home monthly income, $6,666 plus $1,200 net rent after property tax and management fees for a condo they own for rental purposes, gives them a monthly purse of $7,856 to spend. They hope to retire with $4,000 a month in after-tax income. They worry that they may not be able to meet this target.

Before they give up their careers, Catherine wants to take a year off for a sabbatical to study Renaissance music. She and Hugh have also considered a partial retirement at 55, gradually moving into retirement at 65. They worry that their standard of living would tumble.

“I want to devote my time to my passion in music,” Catherine says. “It would produce no meaningful income, but it is my dream. The question we have is whether we can afford it and what it will mean for our retirement.”

Adding to complications, their house, with a present estimated market value of $580,000, is going to be expropriated by their municipality for a public works project. The expropriation would likely pay a bonus over the home’s estimated market value. They could use the cash to pay off their $239,000 mortgage, saving $2,053 in monthly mortgage costs and possibly reducing related costs of home ownership. That would add to their liquidity and mobility. Thus the couple’s question — what would a sabbatical do to their retirement plans? — has a real estate twist.

The planner’s perspective

Family Finance asked Benoit Poliquin, chief investment officer of Exponent Investment Management Inc. in Ottawa, to work with Hugh and Catherine in order to match future income with future spending. “The issue is liquidity, the ability to pay for day-to-day expenses,” he explains. There is some flexibility in the current budget and there certainly would be room for adjustment in the future retirement budget, he notes.

Family Finance asked Benoit Poliquin, chief investment officer of Exponent Investment Management Inc. in Ottawa, to work with Hugh and Catherine in order to match future income with future spending. “The issue is liquidity, the ability to pay for day-to-day expenses,” he explains. There is some flexibility in the current budget and there certainly would be room for adjustment in the future retirement budget, he notes.

They will still have Hugh’s income, $4,266 a month, and their $1,200 net rental income. Catherine will continue to receive $1,500 a month from her company. The average tax rate on her income, $18,000 a year, would be negligible. Therefore their cash flow would be about $6,900 a month, more than enough to cover expenses of $6,361 a month if they tighten their belts just a little, say by cutting back their present $600 a month for travel.

Making the most of expropriation

The wild card in the calculations is the windfall from the forced home sale. They expect a cheque of $1.2 million from the expropriation. The house is their principal residence, so no capital gains tax will be due. The couple will need to find a new place to live, perhaps a home with a $600,000 price tag. That would leave a balance of $600,000. Take off the mortgage debt, $239,000, and they would have $361,000 which could be invested in stocks with a yield of about 3.5% a year. That would be $12,635 a year.

That income plus their eventual payments from the Canada Pension Plan, which will pay them each approximately $8,946 a year at 65 – that’s 70% of the maximum benefit, $12,780 a year in 2015, and Old Age Security at age 66, $6,765 a year each, and $6,000-a-year income from $200,567 of present financial assets at 3% per year after inflation adds up to $50,057 before tax. Add rental income, $14,400 a year, and their total income after age 66 would be $64,457 before tax. With careful splitting of eligible pension and investment income, they could pay 10% average tax in B.C. and have $4,834 a month to spend in 2015 dollars.

Retirement finance

If Catherine returns to work and Hugh stays with his career for another 11 years to age 65, a lot will change. At present, the couple generates a monthly surplus of $2,020. If those funds are invested to yield 3% after inflation, then in 11 years they would have accumulated $319,800. That sum, growing at the same 3%-a-year after inflation, could pay out all capital and interest over the next 30 years to age 95 at a rate of $15,840 a year, pushing total retirement income to $80,300 before tax ,or about $5,900 a month after 12% average income tax.

That after-tax income would sustain their way of life based on $3,393 present monthly cash flow after elimination of $2,053 monthly mortgage payments, TFSA and other monthly savings of $2,020 and no payments to Hugh’s aged mother after she passes away. The couple could make application for postponement of B.C. property taxes on seniors’ principal residences and thus save $300 a month in local property tax. The charge is 1% a year. Owners settle up with the government program when the property is sold. With these adjustments, their after-tax income would certainly cover $3,093 a month of expenses and leave ample money for travel, purchase of one newer car – they would need only one – and savings for rainy days.

Adjusting investments

They might also switch from their clutch of mutual funds to lower fee Exchange Traded Funds. The switch could save perhaps 1% a year. To make that work, they would have to learn the ropes of investing, do background study in accounting, economics, and so on. Or pay someone to do the ETF picking. The choice might save $2,000 to $3,000 a year if they adopt a DIY investment strategy and if it is successful.

Which will it be? It comes down to a choice of working for the future or cutting back work now and having a less materially prosperous future but perhaps a more fulfilling present. A spreadsheet can’t make what amounts to a philosophical decision about work vs. retirement, but a risk analysis can suggest that a great deal can change in the 40 years the couple might be retired if they begin to slash their income at age 55, soon after the end of Catherine’s sabbatical.

In merely financial terms, the value of postponing retirement is not only additional accumulation of savings and potential investment gains, it is a shorter period to death to consume assets. A middle ground of working more years and ceasing work is, of course, more vacations or perhaps less work. Either way, it’s worth considering, Mr. Poliquin says.

Contact [email protected] for a free Family Finance analysis

Click here to see the original article