See article in the Financial Post by clicking here…

Situation: Retired woman in a condo demanding special assessments for repairs fears she’ll go broke as her expenses rise

Solution: Cut spending on luxury car and travel, insulate portfolio from rising interest rates, keep condo for late life sale

In eastern Ontario, a woman we’ll call Beatrice, 72, has been retired for a decade. She’s got a life many would envy. She has a pleasant two-bedroom condo with a view of rolling hills. It’s fully paid for and she has no debts other than credit card bills she pays each month. She skis avidly in the Laurentians in the winter, hikes them in summer, has lovely trips to Europe every couple of years, yet she worries that she can’t maintain her way of life a great deal longer.

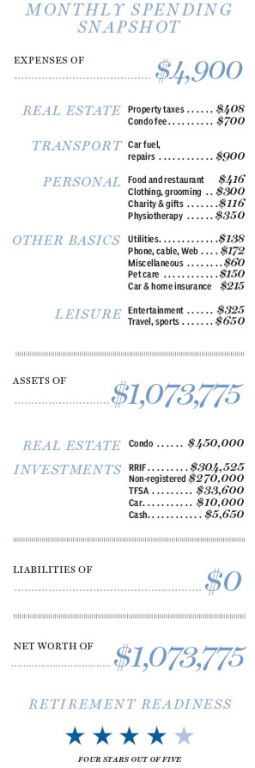

The problem is costs which she sees eating up her $4,900 after-tax income and tax rules which force her to deplete her capital. Her condo board has hit her for $4,000 for building repairs and injuries suffered in a skiing accident are forcing her to pay $350 a month for physiotherapy.

“It is difficult to predict the additional costs that I may encounter should I live to 80 or longer,” Beatrice says. “So I need to stretch my resources. I have to ensure my assets will carry me, even though my living costs will rise and the government’s payout rate from my RRIF will run my investments down.”

Family Finance asked Benoit Poliquin, a financial planner and chartered financial analyst in Ottawa, to work with Beatrice. “Her recent skiing accident has brought home to her the fragility of her plans,” he says. “She has to cut some discretionary spending and raise investment returns. And she can do those things.”

There are two sets of components of Beatrice’s budget – fixed costs, such as the $700 she shells out each month for her condo’s maintenance, plus property tax, $408, and then there are discretionary costs such as the $900 a month she spends keeping her Jaguar running. As well, there is her travel and sports budget, entertainment and sports clothing and other gear which, together, add up to almost $1,300 a month. Some of that is the higher cost of travelling single on cruises she occasionally takes. Most of her costs are just her preference for living well at home and when away from home.

Projecting Beatrice’s income for the next 20 years, it is clear that while her defined benefit pension, CPP and OAS will make up 56% of her future income, the balance, 44%, will depend on her portfolio’s ability to keep up with her cost of living. Assuming that her investments return 3.0% after inflation and that her defined benefit pension, CPP and OAS keep up with inflation, she will nevertheless see erosion of her net worth. Her condo is now 42% of total assets. RRIF payout rules will run down her financial assets, so the condo will grow to as much as 60% of her assets later in life, depending on real estate price trends. The rules will cause growing asset imbalance, Mr. Poliquin says.

Beatrice could raise her financial assets by saving some of the income she spends. She could cut down on travel and lavish spending on her car. Travel is not something she wants to parts with, however. She allows herself one special trip every two years to Europe. It is one of her great pleasures. Sports, mainly hiking and skiing are not expensive on their own. However, maintenance on her Jaguar is another matter. She is spending in a year $10,800, which is more than its $10,000 book value. That is, Mr. Poliquin says, an outrageous layout. She could get a good new compact for two years worth of her present maintenance spending and have a dependable vehicle with a warranty. A good used compact a year or two old might cost just a year and a few months of present car spending. So cutting costs is essential as a way to free up income for, among other things, saving to slow the erosion of retirement capital forced by RRIF payout rules. At present, she saves nothing.

This year, Beatrice will get 7.48% of total RRIF assets distributed to her by rules set by the Department of Finance. The distributions will rise to nearly 9% when she is 80 and 13.6% when she is 90. In bull markets, stock indices can beat these payout rates and sustain capital for several years. At age 94, the RRIF has to pay out 20% of its assets each year.

As RRIF payouts rise, she can save her growing surplus for later years when the RRIF and other assets may be depleted. She has maximized her Tax-Free Savings Account contributions in previous years but has suspended them at present. If she cuts the combination of travel and car maintenance costs, which presently eat up about a third of her budget by just $500 a month – most of that could come from her lavish spending on her car — she could save about $6,000 or more a year. That money could allow her to resume TFSA contributions at the present maximum of $5,500 a year.

Income and spending management

Beatrice’s portfolio is a model of well-chosen stocks, some exchange traded funds which track the U.S.–based Standard & Poor’s 500 Composite, the broad Canadian bond market and several commodity indices.

The question is what lies ahead, Mr. Poliquin says. The excellent performance of Canadian stocks in the last few decades has been driven by falling interest rates, among other factors. When rates do rise, Beatrice’s broad Canadian bond market index is sure to lose value. Moreover, a stock and bond market contraction is likely to occur in the next ten years, just as the payouts from Beatrice’s RRIFs are rising. So building up savings by not spending the rising payouts from her RRIF is vital, the planner says.

There is also a tax issue. A single person, Beatrice cannot split pension income with anyone and thus has to pay relatively high income taxes. She is already close to the trigger point for the OAS clawback, $71,592 in 2014, and the rising payouts required by RRIF distribution rules on top of increases in indexed income from her job pension, CPP and OAS and dividend increases in non-registered accounts may push her over the trigger point in the not-too-distant future.

She can step aside from stock and bond risk by using guaranteed investment certificates in the place of bond funds that make up 40% of her portfolio. GICs will not lose value no matter what interest rates are doing. In the alternative, she can shift from bond index funds that are vulnerable to interest rate gains to bond ladders, especially ladders of investment grade corporate bonds. These ladders roll maturing bonds into new issues and thus climb rising interest rates, he notes. The 60% of portfolio value she holds in equity mutual funds will fluctuate with the market, but stocks tend to pace inflation. And she needs the guidance fund managers provide.

Beatrice’s condo, though likely to impose expenses when her board requires repairs, will tend to rise in value with inflation. Even if her RRIF is depleted, she can turn to her substantial holdings of non-registered assets or sell the condo and thereby obtain money for an assisted living home or even a home with nursing care. At 92, with most or all of her RRIF paid out, and much of her TFSA and her non-registered assets consumed, the condo should have a market value of $722,500. Mr. Poliquin predicts. Its sale would pay for a decade of assisted living.

“Her situation appears more grave than it is now, but if Beatrice does not cut some costs and shift spending to saving to compensate for the RRIF payouts, she will be in trouble in future. Fortunately, she has the time and the ability to cope with these problems. If she does save the increasing surplus of income from RRIF payouts, invests them as suggested, and cuts her cash drain on the car, she will be able to get to 90 or later with much of her present way of life with travel and much of her hiking and even perhaps skiing intact.”