Preferred Shares are often misunderstood and often misused

The financial crisis of 2008-2009 cut significantly into the portfolio values of stock market investors in Canada and around the world, motivating many investors to seek the shelter of safer, less volatile investments. Often preferred stocks were the refuge of choice. That shift in strategy, combined with the significant need of Canadian banks and insurance companies to raise capital to offset the impact of the turmoil and asset write-downs stemming from the global melt-down, spurred a dramatic resurgence in demand for preferred stock.

Canadian brokerages firms, some of the largest of which were bank-owned,

were the primary promoters of these securities. Many of these issues will be coming due over the next year and many investors will have decisions to make. Should preferred shareholders reinvest in this asset class or look at common shares: After all, preferred shareholders missed out on the rally for common shares since the 08-09 crisis.

Since many invested in preferred shares as a shelter, we should ask if this class of share does indeed offer the protection investors were seeking and, secondly, are the returns offered by preferred shares worth the risk? In retrospect, how has that reallocation to preferred stock worked out for investors over the ensuing five years since the financial crisis?

Common Versus Preferred

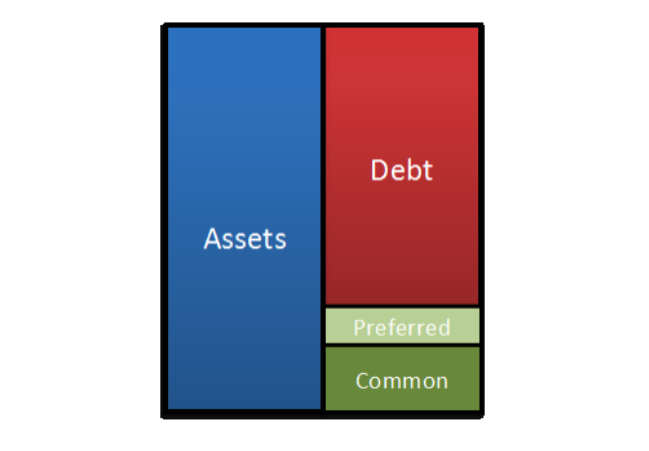

Before we compare the recent results of the two types of stocks, let’s examine the general strengths and weaknesses of both common and preferred stock. Both types of stock provide equity in the underlying company—although only the common shareholders have voting privileges. And both may provide income, although not all common stocks pay dividends. Below you can find an illustration of a typical balance sheet.

There are some other important distinctions between the common shares and preferred shares. Common stock, as its name implies, is generally by far the more common choice among investors because of its potential for price appreciation and dividend growth. But for conservative investors or those seeking a safer alternative during volatile market periods, preferred shares are perceived by many as an investment with less risk and a more predictable stream of income than common shares. We disagree and will show you why.

The first important risk to understand when investing in preferred shares is the interest rate risk. Much like bonds, preferred share prices will move in opposite direction from interest rates, all else being equal. This means that if interest rates for similar bond maturities increase, the price of preferred shares will suffer. Alternatively, should interest rates decrease, preferred share prices will increase.

The most obvious drawback to common stock investing is that it involves price volatility and risk—share prices may fluctuate dramatically, sometimes leading to a significant decline in the market value of stocks, as we witnessed during the economic crisis. Not all common stocks pay dividends—and many of those that do pay dividends often dole out relatively small yields. In fact, the dividend payout for common stocks is not guaranteed, and can decline during periods when the underlying company is experiencing a slump in earnings or revenue.

On the upside, the common stock of companies that are performing well can experience significant price appreciation. Companies may also increase their dividend when business is strong—providing investors with an increasing stream of income that may match or exceed the rate of inflation.

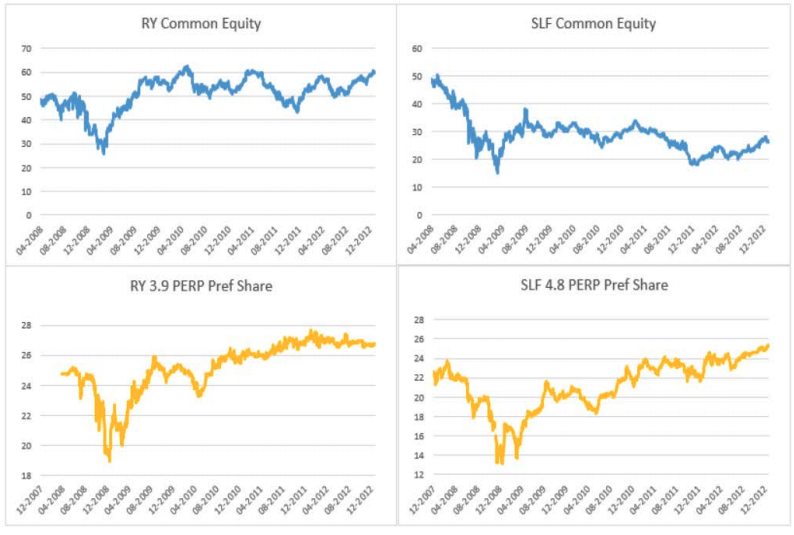

Many market participants perceive that preferred shares have little potential for appreciation and are much less likely to experience a sharp price decline during market downturns. The events of 2008-2009 have debunked this myth…but for some reason, it remains a core belief for some investors.

As illustrated by the graphs above, which correspond to two of Canada’s bluest of blue chip financial stocks, the stock crash of 2008-09 hurt the preferred shareholder as well as the common shareholder. The common shareholder suffered a larger loss, but the preferred shares were still hit and were not the harbor of safety many expected them to be.

While preferred shares typically offer the guarantee of a steady dividend payout with a higher initial dividend yield than common shares, that yield is fixed, so shareholders will not see an increase in their income with the future success of the company.

In Canadian liquidation cases, preferred and common shares are treated equally under CCAA rules unless otherwise decided by a bankruptcy court. From that perspective, there is no advantage over common shares during a liquidation or bankruptcy proceeding for preferred shareholders in Canada. In the event of reorganization or bankruptcy, bondholders and other creditors are first in line for claims against the company’s assets, with preferred and common shareholders sharing equal rights to any additional assets that may be left over, after all bondholders and creditors have been compensated. The Canadian history books are filled with such examples— Royal Trust, Confederation Life, Stelco, Air Canada, Nortel, and Yellow Pages Group, to name a few—in which preferred and common shareholders received the identical treatment.

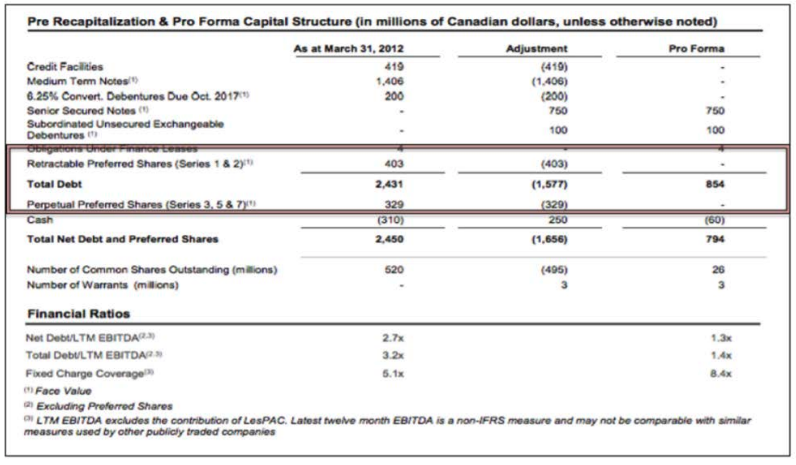

A Real Life Example: Yellow Pages Group

In July 2012, Yellow Media INC (ticker: Y) announced its recapitalization plan in order to improve the capital structure and financial position of the corporation by reducing its debt by $1,527 million. We are interested in this particular case because the company reduced its debt by issuing new common shares and by taking the preferred shareholders equity to pay the principal amounts owed to the debt-holders of the company. As you can see in the Pro Forma financial statement below, there were no preferred shares left after the financial restructuring, which means that preferred shareholders lost almost all the money they had invested in that company.

In compensation for losing their part of equity to debt-holders, preferred shareholders received newly issued common shares and warrants totalling a reimbursement of just 3 cents on the dollar. If you compare that to the 69 cents on the dollar repayment that debt-holders received (composed of cash, new common shares and principal amount reimbursement), you may be wondering if investing in preferred shares is really riskier than investing in common shares of the same issuers.

After recapitalization, common shareholders received warrants and new common shares representing a reimbursement of 1 cent on the dollar. In this case, the downside (loss of 97 cents on the dollar) of the preferred shares is comparable to the downside (loss of 99 cents on the dollar) of the common shares.

On examining this case, we noticed that investing in preferred shares is as risky as buying common shares of the same company. However, it’s well known that common shares have a much greater capital appreciation potential than preferred shares and, therefore, a better risk to reward ratio.

The Outcome for Preferred Stock Holders

As is often the case for investors who switch strategies in the middle of an economic crisis, the decision to move from common to preferred shares during the crisis of 2008-2009 backfired gravely for those investors.

While share prices of common shares have skyrocketed over the past five years, with the overall market value more than doubling during that period, preferred shares have seen only minimal price appreciation.

Investors in dividend-paying common shares have also begun to see an increase in their dividend payout, as profits have not only stabilized but increased as the crisis abated. During that same period, preferred shareholders have seen no increase in their payout.

Even worse for preferred shareholders, some companies have recalled their preferred shares or converted them to lower-yielding preferred shares, while some have also inserted a provision that gives them the option of paying a variable yield which translates into lower income.

So while investors of many dividend-paying common shares have seen a dramatic increase in share value and a steady increase in dividend income, preferred shareholders have not enjoyed either benefit – neither a significant increase in share value nor an increase (and, in some cases, a decrease) in the income they earn from their investments.

Reality Check

To get a clear picture of exactly how shareholders of common or preferred shares would have fared over the past five years, let’s look at some real life case studies.

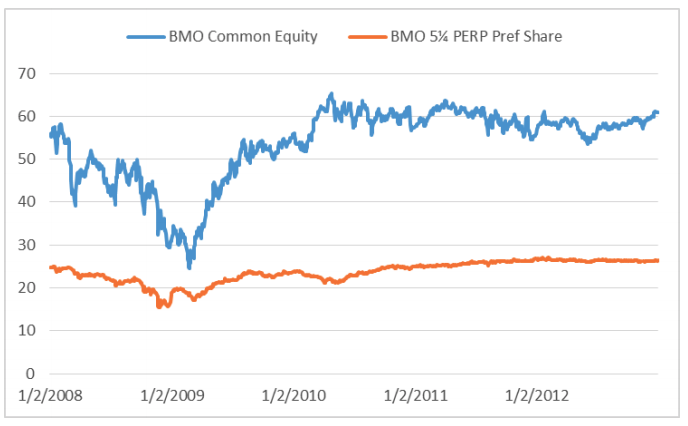

The following charts provide three examples of the difference in performance between the common and preferred shares of three Canadian financial institutions from March 2, 2009 through September 30, 2013 (trough to peak), including Bank of Montreal (BMO), Bank of Nova Scotia (BNS) and Great-West Lifeco (GWO). In the graphs below, common stock is represented in orange and preferred stock is represented in green.

Bank of Montreal

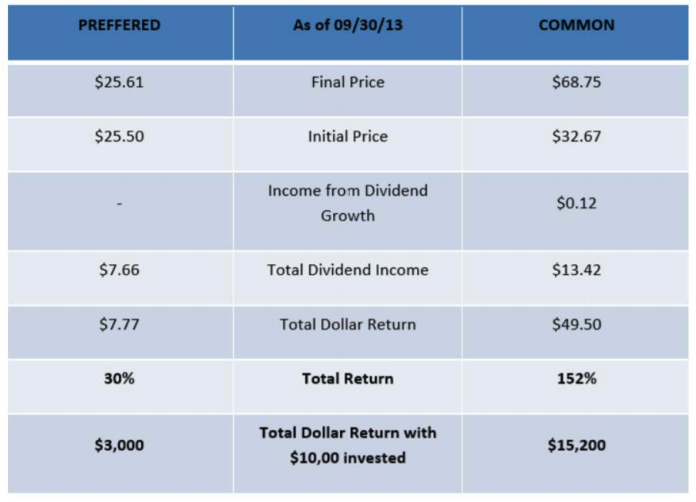

As you can see, while preferred shares experienced almost no appreciation, the common stock price more than doubled from trough to peak. You can also see that, while there was no increase in dividend income for preferred shareholders, common shares had an increase of 12 cents per share. Common shareholders earned almost twice the total dividend income of preferred shareholders and more than six times the total dollar return of preferred shareholders.

In all, common shareholders earned a 152 percent return over roughly a four and-a-half year period, which is more than five times the 30 percent total return of preferred shareholders.