Situation: Parents of three school-aged children must boost RESPs, pay debts and other child costs before retirement

Solution: Use RRSP savings and cash surplus to pay non-mortgage debt, then use liberated money for retirement savings

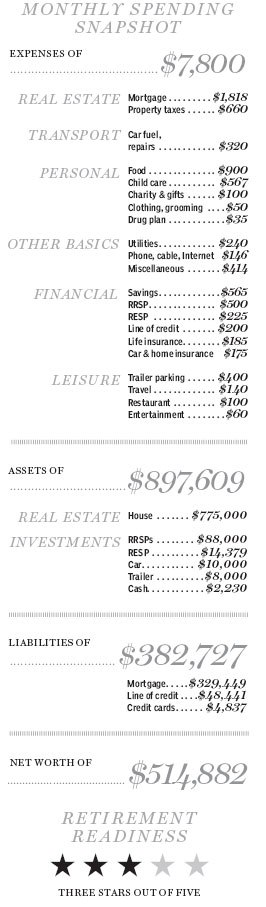

In a small town in Quebec, a couple we’ll call Yves, 51, and Nicole, 45, both civil servants, are raising three children ages 5, 7 and 9 on take-home income of $7,800 a month. Their income pays for the kids’ needs, but leaves the couple with little cash to spare. They have just $88,000 in their RRSPs and cash in the bank of $2,230. They have a $329,449 mortgage that runs to 2035 and $4,837 of credit card debt on top of a $48,441 line of credit. They worry about paying their bills and incurring even more debt for their children’s braces, doing home repairs like building a new bathroom, then retiring when each is 60.

“We have concerns about our level of debt and our lack of disposable income each month,” Nicole explains. “We have so many needs, but no way to fill them.”

Family Finance asked Benoit Poliquin, a financial planner and portfolio manager who is chief investment officer of Exponent Investment Management Inc. in Ottawa, to work with Yves and Nicole. “They have two careers with above average wages and have the advantage of being eligible for defined-benefit pension plans which allow them to retire at 60,” he says.

Debt service costs them $2,018 a month. They also save $500 a month in their RRSPs. At present, they pay $1,818 a month on their 2.95% mortgage with 20 years to go. They pay $200 a month on $53,278 of credit card and line of credit debt at an average 4% interest. The current payments maintain the debt but do not pay it down.

Yves and Nicole should increase the rate of debt payment. They can do that by using the $565 they manage to save each month and adding $500 a month they put into their RRSPs. That $1,065 plus the $200 a month they put into their non-mortgage loans, a total of $1,265 a month will pay off everything but the mortgage in 3.5 years at which time the mortgage will have been paid down to $242,100.

They can then direct $1,265 to the mortgage payment, raising it to $3,083 a month, eliminating the debt in 10 more years, assuming that their present low interest rate does not change. They would be debt-free in 14 years at Yves’ age 65 when their youngest child will be in university and middle child will be finishing and the eldest in grad school or living independently.

Their responsibility to their children for educational costs implies that they should raise their RESP savings, currently $225 a month. The limit for maximizing the Canada Education Savings Grant of the lesser of $500 or 20% of contributions is $2,500 per child per year. Quebec adds another $250 maximum. That’s $7,500 for which they are saving $2,700 or about a third of the limit. They need to find another $400 a month. It’s what they spend on a pad for a large trailer they use for summer holidays. Educating their children is more important than parking a trailer, so that is the sacrifice to be made. They will save $4,800 a year in parking fees, several hundred annually in operating costs, recoup money from selling the $8,000 trailer and operating costs in summer when they use it. The savings will total about $5,500 a year, enough to finance house repairs, especially if Yves and Nicole do some of the work themselves.

The RESP, with a present balance of $14,379, will grow to $108,000 in 8 years when the eldest child begins post-secondary education, with 3% annual growth on top of inflation and contributions of $625 per month or $7,500 a year plus the $1,500 annual CESG plus the $750 annual Quebec bonus. Their total annual contributions will then be $9,750. As each child reaches 18, the CESG and Quebec bonuses end.

The parents can add to the fund at a rate similar to the drawdown until the end of the first child’s second year, then cut their contributions by a third to $5,000 with resulting bonuses of $1,500 then make a final cut of half the remaining contribution rate to $2,500 with $750 bonuses until the youngest child enters university in 12 years. When the youngest child has earned a first degree, the fund should be close to exhausted. Each child should have about $35,000 available for post-secondary education expenses. The kids can supplement their draws from the fund with summer or part-time jobs.

Retirement finance

The cost of raising three children means that their job pensions will have to be the largest part of their retirement incomes. Nicole should have a $40,000 pension at age 60. Yves’ age 60 pension will be $34,000. They can supplement these pensions with RRSP income paid out through Registered Retirement Income Funds. Assuming they suspend RRSP contributions for four years until their non-mortgage debt is paid, the present RRSP balance of $88,000 could grow at 3% a year after inflation to $99,000. Then they could resume $250 individual monthly contributions for five years for Yves and 10 years for Nicole. The accounts would have a total of about $250,000 and could generate $11,300 for 35 years to Nicole’s age 95.

Their total income from Yves’ retirement at 60 to Nicole’s retirement six years later in 2015 dollars would be his $34,000 annual pension, her present gross income of $47,400 a year, $8,179 from Yves’ QPP starting at 60 with a 36% discount from the $12,780 benefit at age 65, $11,300 from their RRSPs and any income they may obtain from a Tax-Free Savings Account they could open with any surplus income they wish to save. That’s $100,879 taxed at an average 25%, leaving them with $6,300 a month.

When Nicole retires six years later at 60, they would lose her income but gain her estimated $40,000 pension, her reduced QPP benefits of $8,179, and, a year later for Yves and seven years later for Nicole, their Old Age Security benefits, currently $6,765 a year. That would make final income apart from unknown contributions from yet to be opened TFSAs about $115,200 or $7,200 a month after 25% average tax based on the assumption of present age and pension credits remaining in force. Present expenses of $7,800 a month will drop by $3,000 with kids gone, debts paid and costs of living reduced.

“Their retirement will be comfortable with more disposable income than when they were raising their children,” Mr. Poliquin says. “Given their present circumstances, that’s a good outcome.”

Financial Post

For a free Family Finance analysis e-mail [email protected].