“Julia can solve her debt problems,’ expert says. ‘The complexity of the process will be rewarded with a dependable retirement income”

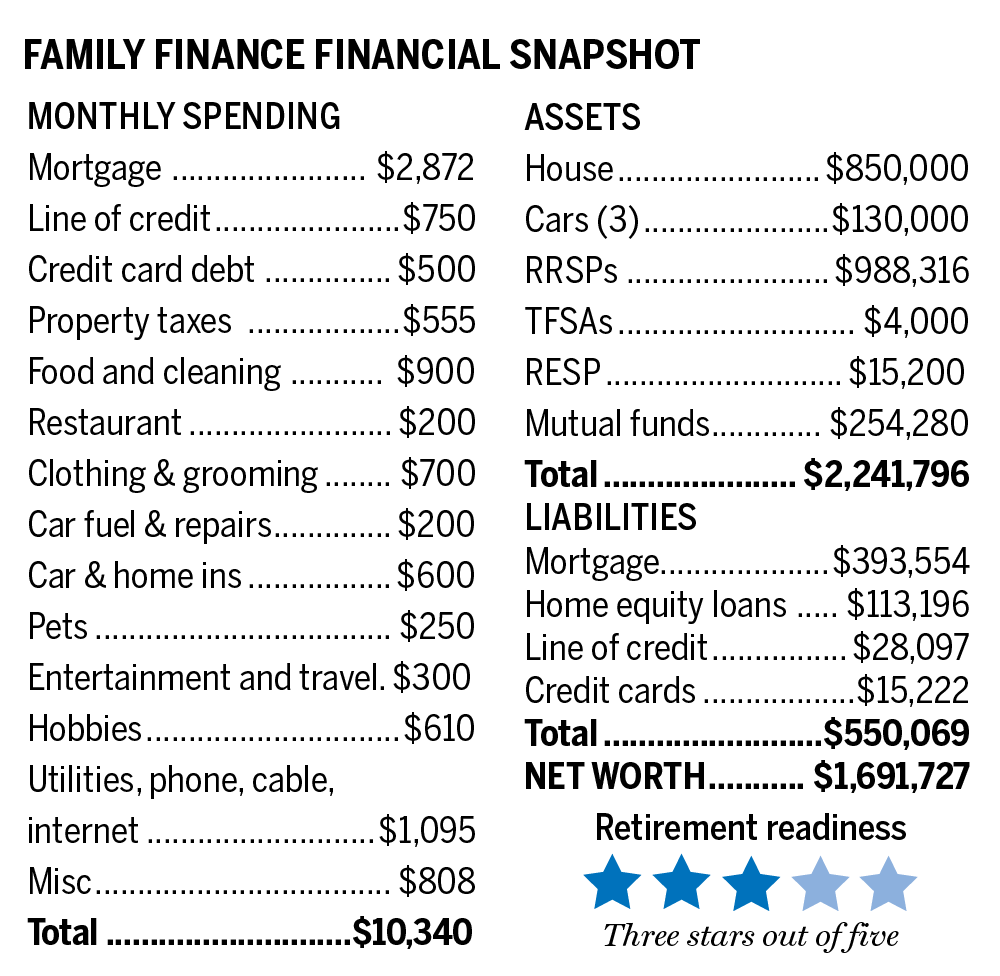

A woman we’ll call Julia, 58, lives in Alberta. Her take-home income works out to $10,340 per month. She has one child in their early 20s living at home and provides a car and other benefits to another in their mid-20s. Julia receives $6,000 in annual child support while the younger lives with her.

Julia would like to retire in two years — if she can afford it. Her assets are substantial: She has an $850,000 house and $1,261,796 in financial assets composed of RRSPs, mutual funds and small TFSA and RESPs. If she starts her retirement at 60, those financial assets, excluding the RESP funds, would be enough to generate $56,325 per year for 35 years if they continue to grow at three per cent above inflation. Julia, who works for a large energy company as a chemist, also expects a $45,000 annual defined-benefit pension, meaning that she is position right now to to collect close to $100,000 in pre-tax income during her retirement.

While that is an excellent foundation, there are some reasons for concern. Julia still has significant debts including a $393,554 mortgage, $113,196 in home-equity loans and $15,222 of credit-card debt with annual interest rates as high as 19.9 per cent. She pays $2,872 per month or $34,464 per year on her mortgage. That’s 28 per cent of her take-home income.

She has tried to take charge of her affairs, but the cost of carrying debt and supporting her family are weighing on her. Will she be able to retire at 60 and keep her home?

Finding a solution

Family Finance asked Eliott Einarson, a financial planner who heads the Winnipeg office of Ottawa-based Exponent Investment Management Inc., to work with Julia. His plan — sell the $850,000 house and pay off the total $506,750 mortgage and home equity loan. Without the $3,622 monthly cost of paying the mortgage and loans other than her credit cards, she would need to replace only $6,718 monthly income in retirement, Einarson estimates. That is something that is well within reach.

If she cuts the kids’ cords of financial dependence, she could reduce $700 per month for clothing and grooming, $900 per month for food and $1,095 per month for utilities, children’s cell phones and web services and car insurance. Under terms of her separation agreement, $500 of child support would end. But it’s a good financial tradeoff. Her monthly costs would go down to about $5,000.

The choice is to keep the big house and remain in debt or downsize, pay off debts, and retire with financial security. Her $850,000 house would bring an estimated $807,500 after five per cent costs. Paying off her mortgage and line of credit would leave her with $300,750 for a hefty down payment or even outright purchase of a townhouse or condo apartment in bustling Calgary or elsewhere in the province.

She can also use her annual $23,000 job bonus to pay off $15,222 of credit card debt, Einarson suggests.

Retirement plans

Two years from now, her DB pension will provide payouts of $45,000 per year. Her RRSP will have grown to $1,048,504 with no further contributions and, with three per cent annual growth after inflation, will be able to generate $47,375 per year for the following 35 years to her age 95. Her $254,280 of mutual funds with no further additions would grow to $269,727 and then pay $12,187 for the following 35 years. That’s $104,562 per year before CPP or OAS start. After 25 per cent average tax, she would have $78,421 to spend each year. That works out to $6,535 per month. That’s more than her estimated cost of living with her adult children moved out.

At 65, she could add CPP at $13,000 per year and OAS at the present rate of $7,707 per year for a total of $125,269 per year before 27 per cent average tax. There would be OAS clawback at 15 per cent of income over $79,845 — that’s about of about $6,800. After regular tax and clawback, she would have $86,646 to spend per year or $7,053 to spend each month. That would cover estimated expenses and leave money for travel or unexpected expenses. Even for gifts to her children.

Starting CPP at 60 would cost her 36 per cent of the $13,000 full annual payout, so it’s worth waiting to 65. Otherwise, over 35 years, she would be forgoing almost $200,000. She would also be slashing the base for annual inflation increases in CPP payouts. Some economies in spending — perhaps charging her child rent — are preferable to this cost, Einarson notes.

Whichever route she goes, Julia should try to raise returns from her financial assets. She has left management of investments to others and not monitored what her advisors’ advice does for her. Her assets are entirely in mutual funds sold by a chartered bank. She is unaware of the fees, how they are charged and, indeed, why she has the present mix of funds. To say the least, taking an active interest in her money and perhaps finding an advisor that does not sell products but merely gives advice could be to her advantage. At her $1-million-plus asset level, she might pay advisory fees of just one per cent of assets under management. On top of index fund fees of 10 to 30 basis points, she might pay just half of present management fees. The fees she does not pay are hers to keep. The savings when compounded for years can translate into big boosts to returns.

Finally, Julia could use growing cash flow to pump up her parched TFSA with a present balance of $4,000.

“Julia can solve her debt problems. Then debt-free, raise her disposable income in retirement,” Einarson explains. “The complexity of the process will be rewarded with a dependable retirement income.”

Retirement stars: Three retirement stars *** out of Five